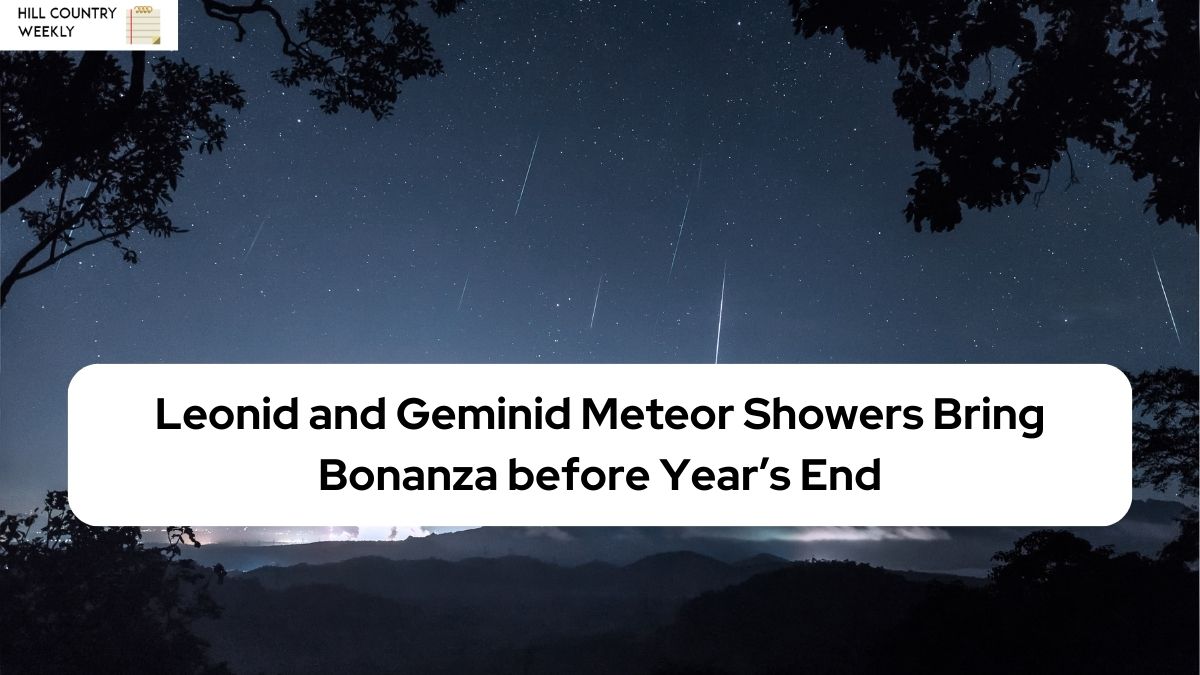

An end-of-year double whammy of meteor showers has the potential to set off spectacular astronomical fireworks.

Two times, the sky has fallen!

As we near the end of the year, you won’t want to miss the spectacular meteor showers put on by the Geminid and the Leonids. Plus, the new crescent moon will dip below the horizon just after sunset for both showers, so the nights will be darker and easier to see.

The Leonids will be at their best tonight, November 17th, so you’ll need to get moving if you want to view them. Still, you can go out tomorrow and run into them. There is still time; the Geminids will reach their zenith on December 14. To be honest, I prefer the Geminid meteor shower. There are around 10–15 meteors per hour that can be seen during the Leonids, but the Geminids are the most spectacular, with as many as 150 meteors per hour passing through Earth’s atmosphere!

However, there are instances when the Leonids raise the volume to eleven, figuratively speaking. Throughout history, their peak has exhibited tremendous upward variation, and credible accounts have been made of meteor “storms” from the Leonids that exceeded 100,000 meteors per hour! It would be thrilling and terrifying all at the same time—about 30 per second. It would appear as though the sky was about to fall.

These storms have their origins in the comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, which is the original source of the Leonids. The comet’s incredibly elliptical orbit around the sun takes approximately 33 years and takes it as far as three billion kilometers—roughly the same distance as Uranus from the sun—before bringing it back into the inner solar system to a point where it approaches Earth’s orbital distance.

Since comets like Tempel-Tuttle are composed of both ice and rock, the vaporization of the ice within the nucleus occurs when the comet approaches the sun. As it dissipates into space, this vapor takes with it some of the comet’s composition, largely in the form of dust and small rock particles but sometimes large pebbles as large as around one centimeter in diameter. This debris is also in a sun-orbiting orbit, somewhat similar to Tempel-Tuttle’s trajectory.

But that “more or less” is significant because it encompasses a number of peculiarities that might make the Leonids of any given year extraordinary—or ordinary.

Midway through November of each year, Earth goes through this cosmic jumble. When this happens, fragments of the Tempel-Tuttle will smash into Earth’s atmosphere at supersonic speeds, causing them to heat up and produce a brief but intense burst of light.

These dazzling streaks across Earth’s atmosphere are par for the course for meteors, but the Leonids add something unique to their display. Tempel-Tuttle moves in the opposite direction of the planets as it orbits the sun, a phenomenon known as retrograde motion. Since we collided directly with the Leonids, their relative velocity as they entered the atmosphere was far higher than that of other meteors, averaging about 70 km/s. Because of their extremely high velocities, the Leonid meteors are more brilliant than those of most other showers.

Tempel-Tuttle produces a fresh batch of meteoroids—space-based particles of debris that become “meteors” when they enter and burn up in a planet’s atmosphere—every time it approaches the sun, which is why the Leonids’ meteor storms are so famous. These streams of meteoroids are pushed away from the comet into somewhat divergent orbits by the combined forces of solar pressure and the gravitational pull of the planets. The number of meteors can increase considerably when Earth travels through a dense stream. Major storms from this stream are not expected again until 2033, the last time being in the early 2000s. Hundreds of meteors an hour might illuminate Earth’s sky at that time.

Although the Leonids this year are not predicted to be particularly active, unexpected surges in activity are always possible. Going out and looking is your greatest choice.

Unlike the meteors of nearly every other yearly shower, the Geminids in December have an asteroid as their parent body, which makes them even more distinctive! Here we have 3200 Phaethon, a roughly 6-kilometer-wide rock. Its orbit brings it closer to the sun than Mercury’s orbit, taking it past Mars but bringing it down to a scorching 21 million km.

For a long time, scientists thought that the Geminid meteoroids originated from rock evaporated on Phaethon’s surface due to the extreme heat of that near flyby. Nonetheless, a new study from this year’s Planetary Science Journal reaches a different verdict. The scientists ran simulations of the particles’ departure from Phaethon in conditions where they were heated by the sun and discovered that their predicted orbit did not correspond to the observed one.

However, the paper’s authors found that the violent expulsion of rock was a better fit with the Geminid orbits when they hypothesized that a tiny asteroid had previously impacted Phaethon. Actually, Phaethon’s orbit is quite similar to that of two other asteroids, 1999 YC and 2005 UD, suggesting that all three were produced when a larger asteroid was shattered in a major collision.

Assuming this to be accurate, each meteor observed during the Geminid period is actually a little fragment of debris from a long-ago collision between two asteroids! That is just awesome.

Although their impact is at a more respectable 35 km/s, the Geminids are still hundreds of times quicker than a rifle bullet since they follow Earth’s general orbit around the sun. Not only does the meteor shower typically have larger chunks, but it can also be rather brilliant, with more meteors per hour.

How can you witness these two heavenly spectacles? You may enjoy the Leonid and Geminid showers—along with all other meteor showers—without the aid of binoculars or a telescope, unlike with many other celestial phenomena. Because meteors move so fast across the sky, it’s likely that you will miss them if you use an eyepiece. For that reason, I recommend against using them.

Rather, seek for an area devoid of artificial lights and anything that block the sky, such trees and buildings. Since meteors can occur anywhere in the sky, finding a dark and clear spot to watch them is ideal. To relax in style, a chaise lounge or blanket are ideal. Naturally, dress warmly! A mug of hot chocolate always brightens my evening.

If you’re on the side of the Earth that faces in the direction that our planet travels, the optimum time to see a meteor shower is after midnight local time. (Imagine being in a rainstorm while driving; the precipitation primarily lands on the front windshield instead of the rear.) Earth grazer meteoroids, which penetrate the atmosphere at a very low angle, are the stars of the Leonid shower and can light up the whole sky. When the constellation Leo rises on the horizon at approximately 11 P.M. local time, the meteor shower’s “radiant”—the point in the sky from which the meteors seem to radiate—is at its best. This is when these Earth grazers are most visible.

A meteor shower is a great reason to spend time outside beneath the stars, and it’s even more enjoyable when you can bring those you care about along. The memory of waking up my little daughter to go outside and watch them is one that I will always cherish. If you get the chance, try to capture some personal experiences when you see asteroids and comets as they make their last pass across our sky.